What are Systematic Reviews

A Systematic Review is a particular research methodology designed to gather and assess the available evidence related to a specific research question, topic, or phenomenon of interest through a rigorous, trustworthy, and replicable approach [1, 2].

It is not uncommon for people to mistakenly conflate traditional literature reviews with systematic reviews. However, systematic reviews have a distinct advantage due to their reliance on a rather concrete, documented process (i.e., a clearly pre-defined review protocol). The Protocol involves several key elements [3, 4], including:

- Specified research question(s);

- A transparent and replicable search strategy for identifying all relevant literature related to the research question(s) and for ensuring rigor in review execution;

- An explicit definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria for evaluating each relevant piece of literature;

- A clear exposition of mechanisms for evaluating the quality of the included literature; and

- A detailed account of the review and cross-checking processes, with the participation of multiple independent researchers to control for researcher bias.

Notes: The systematic review protocol encompasses various components that are indicative of the final report’s structure [2, 4], including the research background, the research questions*, the search strategy*, the criteria and procedures for selecting studies*, the mechanisms for assessing study quality*, the checklist for extracting data, the approach for synthesizing data, the procedure of review and cross-checking*, the dissemination strategy, and the project timetable.

How to perform Systematic Reviews

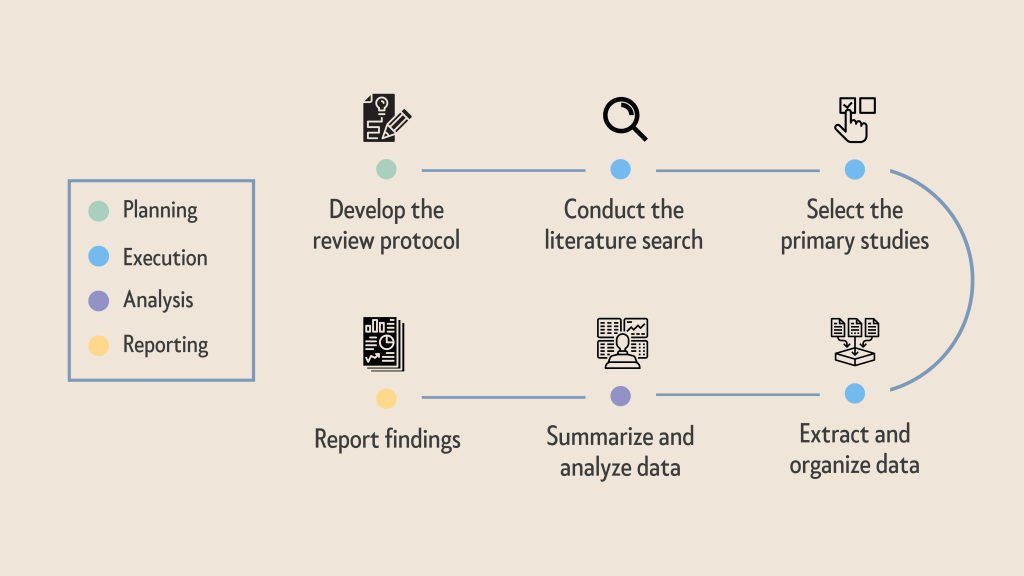

While various systematic review processes may differ slightly, they share a common framework that encompasses four key stages: planning, execution, analysis, and reporting of findings (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: The process of systematic review

Planning

The main objective of the Planning Stage is to establish a Protocol (as mentioned before) that encompasses all the essential information and procedures required for the subsequent stages of Execution, Analysis and Reporting.

Tips

Research Question(s)

To ensure a successful systematic review, it is crucial to formulate the *right* research question(s) in a structured and explicit manner. This will contribute to a more thorough, well-analyzed, and efficient systematic review. Models and frameworks can help researchers formulate *good* research question(s).

Search Strategy

- The synonyms for the determined keywords can be used for building search strings;

- Boolean operators (OR, AND) can be applied to the search strings to create more focused and effective search terms [2];

- The search strings and online libraries employed by prior review studies that were conducted in the same or a related research area can be beneficial for developing a research strategy in a more efficient manner;

- It is crucial to evaluate and assess the planned Protocol before executing it. Experts can be invited to provide their input on the proposed review, or the execution of the Protocol can be tested by conducting a review on a limited number of selected sources. If the outcomes do not meet the expected standards, the Protocol must be revised, and an updated version must be developed [1].

Execution

The Execution Stage is comprised of three essential steps. Firstly, it involves retrieving the primary studies using pre-defined search strings from various trustworthy search engines and online libraries. Secondly, the retrieved studies must be selected based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Lastly, the pertinent data for addressing the research question(s) will be extracted from the selected studies [1]. By adhering to these three steps, researchers can ensure a systematic and rigorous approach to their work, thereby maximizing the accuracy and reliability of the analysis.

Tips

Data monitoring

Data monitoring can also be included in this stage, which entails identifying multiple reports of the same study and contacting authors to obtain missing or unpublished data [4].

Selection Criteria

Examples of study selection criteria [2] for consideration:

- Language

- Journal

- Authors

- Setting

- Participants or subjects

- Research Design

- Sampling method

- Date of publication

Data Extraction

To ensure accuracy and reliability in the data extraction phase, Kitchenham [3] suggests involving two or more researchers in this step and resolving any disagreements through consensus or by consulting additional experts.

Analysis

The Analysis Stage takes place after data has been extracted and involves the process of summarizing and critically analyzing the information in order to address the research question(s) that were clearly pre-defined in the research protocol.

Tips

- The process of data analysis involves the tabulation of information extracted from the studies, for example, methodology, sample sizes, outcomes, and study quality. It is important to structure tables in a way that emphasizes the differences and similarities observed among study outcomes [3].

- Identifying the homogeneity or heterogeneity of study results is also suggested, along with displaying any possible causes of heterogeneity, such as the type of study, its quality, and the size of the sample [3].

Reporting

Upon the completion of these three stages, it is essential to Report the Findings by means of technical reports or scientific papers [3]. Doing so serves the purpose of exhibiting the present state of research in the relevant field and identifying the current challenges and gaps for future research to fill [5].

Useful Tools/Resources

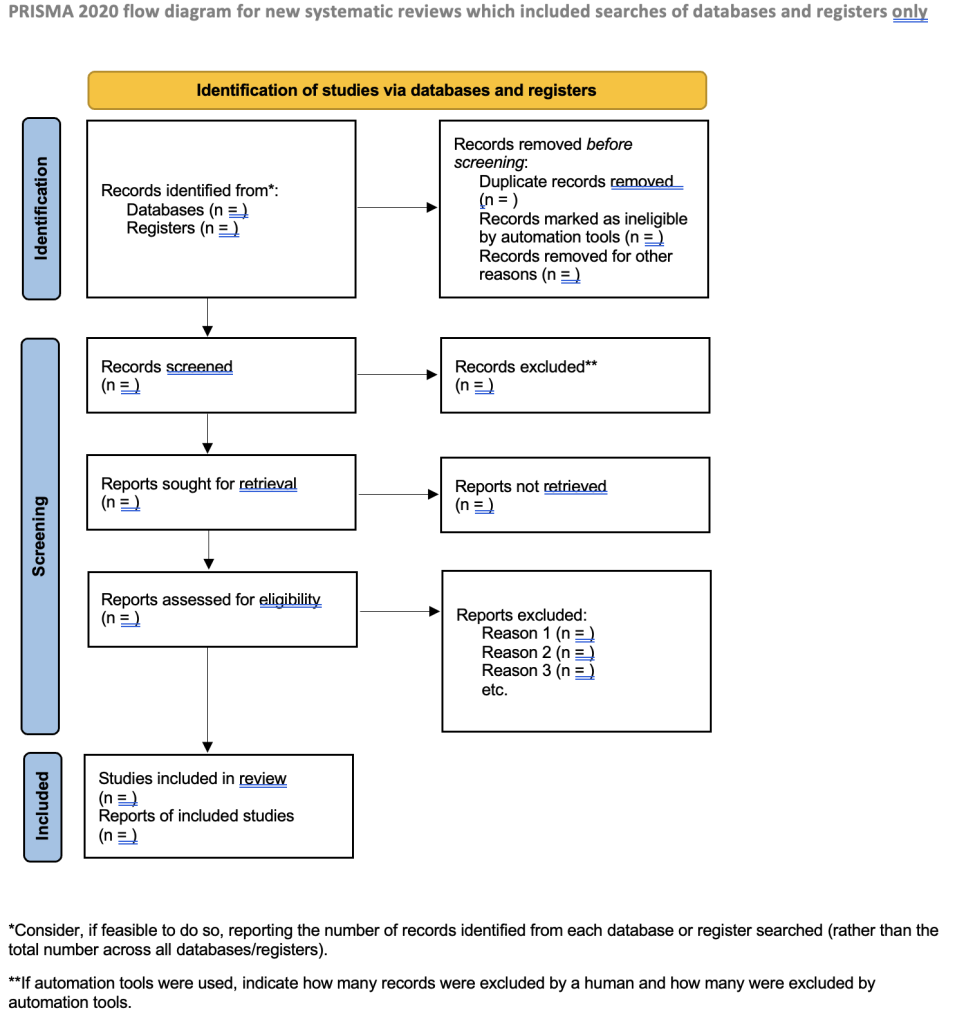

Although systematic reviews offer benefits such as comprehensive coverage, reproducibility, and reliability, their process is more time-consuming compared to traditional literature reviews. Systematic reviews involve multiple stages and require the management of several documents. Therefore, to decrease the amount of manual labour required and enhance the quality of the review, computational tools are indispensable [5].

Figure 2: PRISMA Flow diagram

- M. Gusenbauer and N. R. Haddaway, “Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? evaluating retrieval qualities of google scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources,” Research synthesis methods, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 181–217, 2020

- C. Marshall and P. Brereton, “Systematic review toolbox: a catalogue of tools to support systematic reviews,” in Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, pp. 1–6, 2015

- H. Harrison, S. J. Griffin, I. Kuhn, and J. A. Usher-Smith, “Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in health-care: an evaluation,” BMC medical research methodology, vol. 20, no. 1,p. 7,2020

- C. Kohl, E. J. McIntosh, S. Unger, N. R. Haddaway, S. Kecke, J. Schie-mann, and R. Wilhelm, “Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: a case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools,” Environmental evidence, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 8,2018

Must-Read

- B. Kitchenham and S. Charters, “Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering,” Eng., vol. 2, 2007, Art. no.1051.

- J. Biolchini, P. G. Mian, A. Candida, and C. Natali, “Systematic review in software engineering,” Eng., vol. 679, pp. 165–176, May 2005.

- B. A. Kitchenham, “Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews”, Soft-ware Engineering Group, Keele University, Keele, UK, Tech. Rep. TR/SE0401, Jul. 2004.

References

[1] J. Biolchini, P. G. Mian, A. C. C. Natali, and G. H. Travassos, “Systematic review in software engineering,” System Engineering and Computer ScienceDepartment COPPE/UFRJ, Technical Report ES, vol. 679, no. 05, p. 45,2005.

[2] B. Kitchenham and S. Charters, “Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering,” 2007.

[3] B. Kitchenham, “Procedures for performing systematic reviews,” Keele, UK, Keele University, vol. 33, no. 2004, pp. 1–26, 2004.

[4] M. Staples and M. Niazi, “Experiences using systematic review guidelines,” Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 80, no. 9, pp. 1425–1437, 2007.

[5] E. Hernandes, A. Zamboni, S. Fabbri, and A. D. Thommazo, “Using GQM and TAM to evaluate StArt-a tool that supports Systematic Review,” CLEI Electronic Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 3–3, 2012.

[6] A. Pollock and E. Berge, “How to do a systematic review,” International Journal of Stroke, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 138–156, 2018.

[7] K. S. Khan, R. Kunz, J. Kleijnen, and G. Antes, “Five steps to conducting a systematic review,” Journal of the royal society of medicine, vol. 96, no. 3, pp. 118–121, 2003.

[8] C. Wohlin, P. Runeson, M. Höst, M. C. Ohlsson, B. Regnell, and A. Wesslén, Experimentation in software engineering. Springer Science &Business Media, 2012.

[9] C. K. Pereira, S. W. M. Siqueira, B. P. Nunes, and S. Dietze, “Linked data in education: a survey and a synthesis of actual research and future challenges,” IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 400–412, 2017.